For most years since 1997, I have taught a first year university intro to communication studies course. While I don’t often focus on interpretation of media messages or public relations–there are lots of other things to cover–sometimes it’s a good exercise. To keep myself in shape, I thought I would practice on McGill’s latest announcement about our return to campus in the middle of a raging pandemic and a failing public health infrastructure in Quebec.

Following George Orwell’s famous “Politics and the English Language,” I have translated Fabrice Lebeau’s message that went out yesterday to the McGill community into English.*

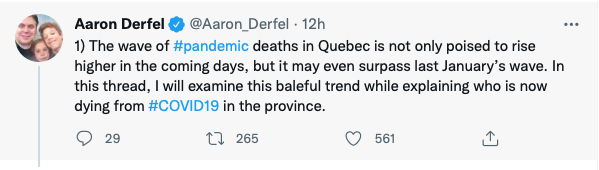

As announced during Premier Francois Legault’s press conference on Thursday, universities and CEGEPS will be allowed to resume full in-person academic activities starting on January 17. The curfew will also be lifted January 17.

McGill will therefore follow its plan to transition to in-person classes for most teaching activities on January 24.

Most lectures with more than 200 students will remain online, as announced previously.

All faculty, staff, and students will need to be in Montreal.

For administrative and support staff:

Staff who need to be onsite to carry out their job functions will continue to come to campus, including staff carrying out administrative activities in support of on-site operations.

Staff who need to be on campus to provide the best support to students or to in-person academic activities (learning, teaching and research) will also be asked to return, with the schedule determined by their supervisor.

Other administrative and support staff will begin to return in the coming weeks, with a timeline for return to be announced soon.

You have to go back to campus on the 24th. Staff with immediate supervisors who believe more fervently in science than bureaucratic directives may have somewhat greater flexibility in their working arrangements, at least in the short term.

New government projections show that Quebec may have hit its peak in cases and hospitalizations will likely soon begin to stabilize, though the situation in the health care system remains difficult. Thank you to all McGill faculty, students and staff contributing to the fight against COVID.

The government has stopped testing people for Covid and our hospitals and emergency rooms are full beyond capacity. Our premier would like it if the rate of infection were to decline soon. There is no need to wait and see if their projections pan out. Now is the time to return to campus.

Thank you to all our hard working employees.

We have been receiving many emails and getting other feedback. People are divided in their opinions about in-person activities. While online learning has its place, many are exhausted by it and feel isolated. Many students and instructors are very eager to come back in-person. But some people are very anxious about in-person activities because of the transmissibility of the Omicron variant.

People are talking. Some people are saying that they very tired of being in a pandemic and are tired of all the safety measures. Other people are saying that they are very tired of being in a pandemic and tired of all the safety measures, and are also concerned about dying or becoming permanently disabled from–or infecting a loved one with–a virus that is not currently well understood or under control.

We understand these concerns.

Both sides have valid concerns.

We will be communicating throughout next week to answer various questions, discuss our safety measures, and address your concerns.

Omicron is indeed highly transmissible and presents differently than previous variants, but vaccination still provides strong protection against severe illness. If you are worried about yourself or those around you, get your third dose as soon as possible. Three doses of vaccine prevent upwards of 70% of transmission. Nearly all COVID cases in triply vaccinated people are not severe.

Even double vaccination provides a strong level of protection against severe illness requiring hospitalization, and more than 96% of our students are now vaccinated with at least two doses.

The risk to a small number of our staff and students is a risk we have to take at this time because we are tired of being online. Since there is very little research on long Covid from Omicron, there is no reason to worry about it at this time.

A high level of vaccination, plus the many other layers of protection McGill has in place, makes us confident that we can continue our commitment to in-person academics and maintain a safe environment on our campuses.

We will maintain a safe environment for nearly all members of our community.

Booster shots now open for everyone 18+

All adults are now eligible to receive a third COVID vaccination if it has been at least three months since your last dose. Santé Québec recommends that you get the booster shot, even if you have recently had COVID.

Three doses will soon be required to be eligible for a vaccine passport, so we advise you to get your booster shot as soon as possible. More information here.

Rapid testing available for symptomatic individuals living in residences

As the government is now restricting rapid tests to people with COVID symptoms, we have transitioned to testing symptomatic individuals living in downtown residence buildings. Three rapid test sites are opening today.

All residents should have received an email with further details and how to book a test. Testing will expand to Macdonald campus residences in the coming weeks.

We are restricting the rapid tests to symptomatic people living on campus, as we do not want to encourage members of our community to travel to the University if they are symptomatic. If you have COVID symptoms, self-isolate and follow these instructions.

Get a booster shot.

Do not test if you might have been exposed. It is important to conserve tests. Even though this virus is extremely contagious, only test if you have symptoms.**

If you have been exposed to the virus, but are asymptomatic, you can come to campus.

Extracurricular activities must be virtual

Danielle McCann, Quebec’s Minister of Higher Education, announced via Facebook that, for the moment, extracurricular activities would need to take place virtually.

Report your symptoms or positive COVID diagnosis to the Case Management Group

Call 514-398-3000 if you have had a positive test OR if you are self-isolating because of COVID-19 symptoms AND have been on campus in the 48 hours before your symptoms began.

Reporting is extremely important in helping us identify and manage any possible outbreaks on campus.

The case management staff will also provide information to you about next steps and resources.

[This section appears to be written in English.]

Take care of your mental health

It is your responsibility to take care of your mental health.

The uncertainty and isolation from the COVID pandemic can take a toll on your mental health. We all need help sometimes. If you are feeling overwhelmed, anxious or depressed, resources are available to help students and staff.

Because we believe mental health is important, we launched a program called “My Healthy Workplace” in the middle of a pandemic. It’s a web portal.

In the midst of this uncertainty, please remember to take a break and do something relaxing that is not in front of a screen. Go outside, call a friend, meditate – whatever works for you. I hope to see you very soon.

Do not rage at doublespeak appearing on your screens, or the fact that your employer, who also employs some of the world’s leading epidemiologists, is not taking an extra week or two to see if the infection rate is actually ebbs. That would not be good for anyone’s mental health.

—

Notes:

*Since I’m writing in Quebec, here’s your obligatory clarification that this isn’t about the quality of anyone’s English fluency. In fact, the announcement shows the deft use of English to, in Orwell’s words, defend the indefensible.

**The province has ceased offering PCR tests to most of the population and therefore can no longer accurately track Covid rates.

—

Read more here for the context in which McGill announced that everything was about to get better: