It’s Sunday. Time to watch football and cook a lot.

Here are some vegan/low iodine things we’ve been making. Recipe links are posted when available. I’m too lazy to type things out if they’re not already typed out online or in our electronic recipe book already (there’s a lot of copy/paste in this post, but it’ll be new to you). Also, I had planned to do this daily but that’s too much. So instead you get massive weekly updates, like this one.

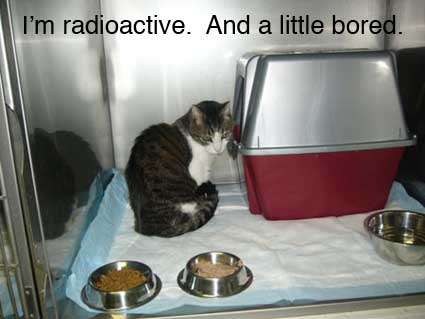

When on the low-iodine diet you can either make everything yourself, or eat boringly. I lean toward the make everything myself because it’s frankly enough unpleasantness to put a giant dose of radioactive material in my body at the end of this. Why shouldn’t I have a little fun now? The other thing is even if it’s boring, I still have to plan it out.

Dinner #1: Stew and sides. We made this Friday night.

–>Bulgarian Red Pepper Stew from Sundays at the Moosewood. We served it to guests and got another meal out of it.

Normally you have it with sour cream or yogurt. Since I can’t do that right now, I went for cashew cream courtesy of the Post Punk Kitchen and Isa Does It.

Soak 1 cup cashews in a bunch of water overnight. Drain. Put in the blender and puree with two cups water, a little fresh lemon juice and salt.

Serve the stew and put just a small spoonful of the cream into the bowl and you get some nice creaminess. I don’t find cashew cream all that good by itself but it works to add texture.

Our side was roasted brussels sprouts and cauliflower (also made a ton and ate leftovers for another meal):

Slice brussels sprouts in half

Cut cauliflower into florets

toss with olive oil and salt

roast at 425 degrees about 45 minutes or until the sprouts are melty.

I also made another no-knead bread, this time with 1 cup each of white, wheat and rye flour.

Coconut Milk Ice Cream

For LID people, you need to check the label for additives. The kind I got was organic with guar gum as the thickener. That’s LID-approved.

Two cans coconut milk

1t vanilla

1/2-3/4 cup sugar (to taste)

Put all the ingredients in a blender. Blend. Put blender jar in fridge for a couple hours. Then freeze it in your ice cream maker. We served it with berries. You could also flavour it however you like. Tonight we will try it with cardamom and rose water if we have it (to go with the Indian).

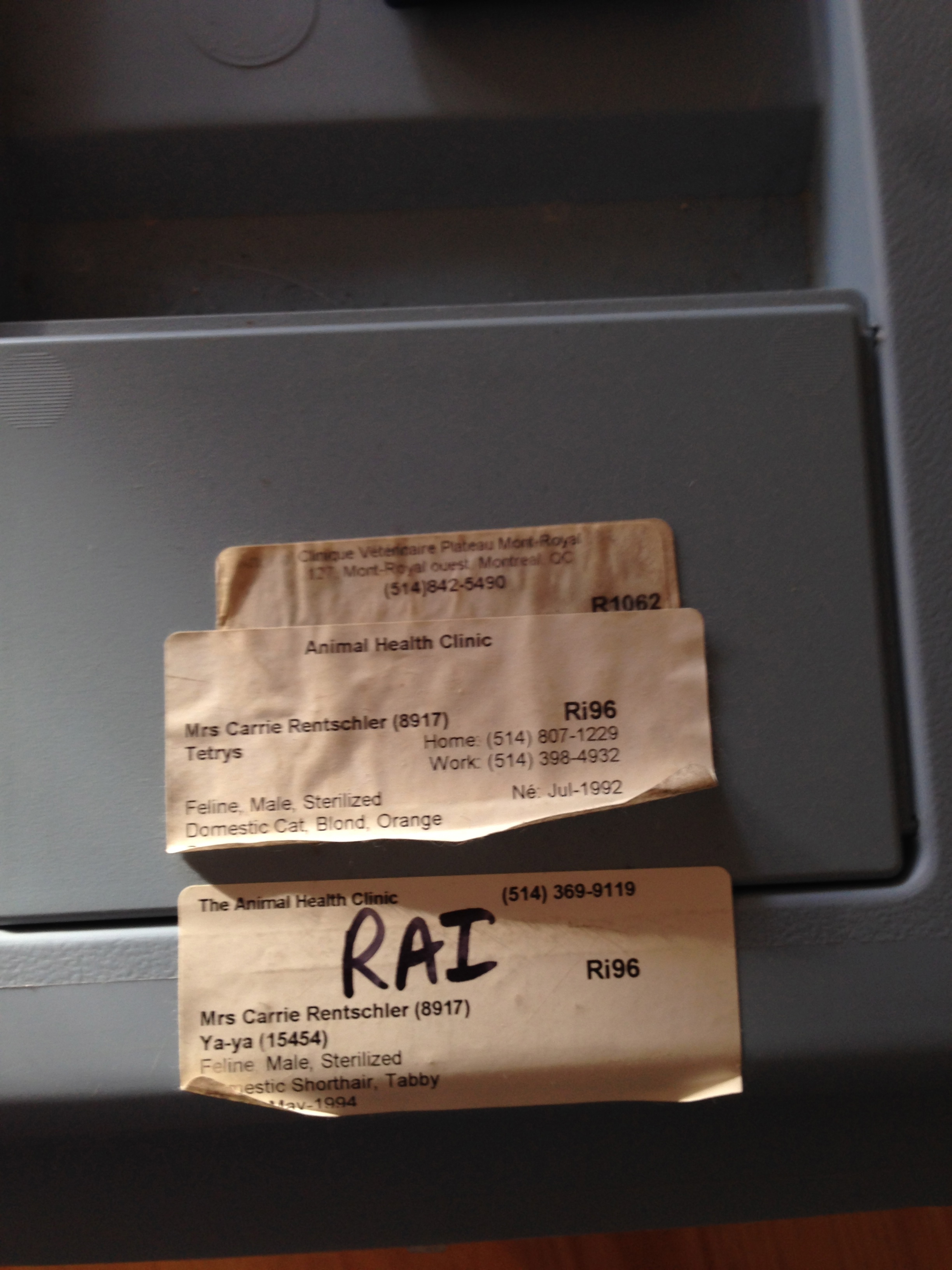

–>Corn muffins from Isa Does It (on a quick look online I don’t see a similar recipe). We both loved them for breakfast this morning. We had to substitute Yu rice milk for soy milk since YU is the only LID approved non-dairy milk in Canada (unless we made it ourselves).

–>Tacos (aka “breakfast tacos” aka regular tacos, but eaten at different hours than usual)

Fresh tortillas with no salt in them are fair game. Then it’s off to the races. I used the following veggies but any will do:

Onions

Garlic

Poblano Peppers (tons, they’re from the market)

Nance Carrots

I stir-fry them in oil, and add chill powder (we just happen to have a little free jar from Penzy’s that doesn’t have salt in it–otherwise I was prepared to roast and grind peppers), cumin, salt, pepper, and a little paprika. I do the spices visually. A big dusting of chill powder, and less of everything else to add a few “notes” to the flavour.

Then I added some seitan, which is the only veggie protein you can have on the low iodine diet. (Lentils are also an option, but there are lentils in the stew and lentils in the Indian, and so I wanted a break.)

Tacos were eaten for lunch Sunday and then will be rotated across different meals as the inspiration strikes.

I took the leftover cashew cream and made an experimental “nacho sauce” for the veggie tacos. It’s based on this recipe, except I substituted mustard powder for miso since I can’t have miso (homemade mustard would have been better but was too much work). I skipped all the veggies except for garlic, but I did put in a dried chipotle. The result is not exactly like nacho cheese sauce and not amazingly delicious straight, perhaps because I didn’t follow directions properly.I found it a bit strongly flavoured as a background to the tacos and not in a good way–I think I might just whip up more regular cashew cream instead, and/or make pickled onions since I can’t put on a vinegar based hot sauce.

Baked Seitan (adapted from Cooking with Seitan, a cookbook I bought mainly because the title is fun to say out loud)

(Skip this if you’re gluten free. This would be a bad thing to eat in that case.)

Preheat oven to 400 degrees.

2 cups gluten flour (you can make your own but it’s a hassle)

1 cup veggie stock (I used unsalted), cooled

1 cup rice milk (soy or whatever ok if you’re not LIDing)

1/2 t each garlic powder, dried onions, salt

Stir up the dry ingredients in a bowl, stir in the wet. The dough should be spongy and not too sticky. Roll into a log with about 3″ in diameter. Slice into 1/2″ cutlets. Lay them out on an oiled baking sheet. Bake for 10 minutes, oil the tops, flip and bake 10-15 minutes more. Seitan cutlets will get a bit puffy. This recipe is pretty bland but the texture is good and since I want to use them in Mexican and other recipes, I didn’t want to flavour it one way or another. For the tacos, I sliced the cutlets thin, added them in right before the veggies were done, dumped in all the spices and about half a cup of water with the heat on high and the seitan soaked up the flavour. Normally, you’d do something else with the cutlets, like simmer them in broth or stuff them.

–>Indian dinner This will make tons of good leftovers for the week that can be reheated in a few minutes. Key when you’ve got lots of late afternoon meetings like I do.

Biryani (adapted from Neelam Batra’s book)

6 medium cloves garlic, crushed (lots)

1-2” piece fresh ginger, minced (lots)

1/2 c fresh cilantro, chopped

1c tomatoes, chopped

1 large onion, chopped

6 or more cups fresh vegetables (carrot, cauliflower, bell pepper, frozen peas[leave out the frozen peas for LID], etc) — we got a beautiful cauliflower from the market, and have some left over broccoli and string beans. And some more bell peppers and carrots.

1 cake tempeh, cubed [skip if on LID–no soy allowed!–we made the lentils below for protein instead]

2t garam masala [for LID, you need a masala without salt–we have a rose masala with no salt that we have been wanting to try]

2t ground cumin

1t crushed red pepper

1-1.5t salt

½-1t turmeric

oil for stir frying (I recommend coconut oil)

+

2 cups brown basmati rice

4 cups water

5 black cardamom pods, lightly pounded

1 cinnamon stick

1.5t cumin seeds

1t salt

oil

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

Heat oil in saucepan big enough to hold all the rice and water. When hot, add cinnamon stick, cumin seeds, cardamom pods. When they pop after a few seconds, stir in rice and water, crack a little pepper in (or use a few whole peppercorns if you dare), bring to boil, then simmer for 45 minutes or until done. Rice can be a little wet when it’s done.

In a very large, oven-safe dutch oven, stir-fry vegetables and tempeh in the usual order (hardest to softest), add spices, add tomatoes and coriander at the end and cook a few minutes more. Stir in cooked rice, put in the oven for 15 minutes. (or transfer to baking dish if you don’t have anything that works on the stove and in the oven).

Watch out for cardamom pods and cinnamon stick when eating.

To go with it, we made the everyday dal from Curries Without Worries, using red lentils. (this is the only adaptation I’ve found online, we do it a little differently)

–> Dinner if necessary. Stir fry as yet to be determined. With rice. Quick and easy, veggies available at the corner on the way out of the metro and left over seitan. As long as it’s not soy-based we’re good. Perhaps Carrie or I will make this:

Carrie calls this “Jon’s Dry Coconut Curry Delight” which means, when she makes it, I like to call it “Carrie’s Jon’s Dry Coconut Curry Delight”

1 large onion

1 leek

1 sweet bell pepper

2 cans mock duck (or 1 large cake tempeh or tofu) [for LID, it would have to be home-made seitan or just put lentils in the rice for protein]

½ cup desiccated coconut

oil for stir-frying (coconut recommended)

1.5 tsp black mustard seeds

1.5 tsp cumin seeds

¼- ½ tsp asafetida

1 dried hot chili or ½ tsp red pepper flakes or to taste

2 tsp good curry power [LID: make sure it’s a curry powder without added salt–and hey, we have fresh curry leaves in the freezer so we might try that]

½ tsp salt or to taste

Slice onion and leek thin, chop the bell pepper small and cut the protein as you see fit.

Heat the oil in a large skillet. When hot, dump in the mustard and cumin seeds. Once they start to pop (which will be almost immediately if the pan is hot; be ready), add the onion, leek and bell pepper. Sautee until almost done. Add the protein and coconut. Then add the spices and salt to taste. Serve over rice. Goes well with fruity hot sauce and yogurt if you’re not on the LID.

Other notes for LID people finding this via web search:

For lunches at work, I’m going to bring in leftovers some days and other days eat a variety of portables: we’ve got a metric ton of hummus and acres of carrots, fresh fruit, some nut bars from the corners with no salt in them, more muffins, and the like. I’ll also do PBJ at least once, since that’s easy, filling, functional, and portable.