New Text

Here’s a new interview with me about Diminished Faculties.

And I have a newish piece with Mehak Sawhney on machine listening and the will to datafy. I’ll get it up on the site, but if you’re at a university, your library should get Kalfou. Happy to email PDFs to people, too. Just ask.

“I’m so busy”

In my experience academics love to talk about how busy they are. It can be a sort of performance/or olympics thing on social media or in conversation, a kind of protestant/grind culture thing (“spring break is a great time to get caught up on my email”), or a status game. Sometimes people are genuinely excited about what they’re doing and just reporting that (on social media this can be read in an unnecessarily hostile manner). We’re not unique if you look at hours logged in some corners of the tech industry, law, medicine, and other professions.

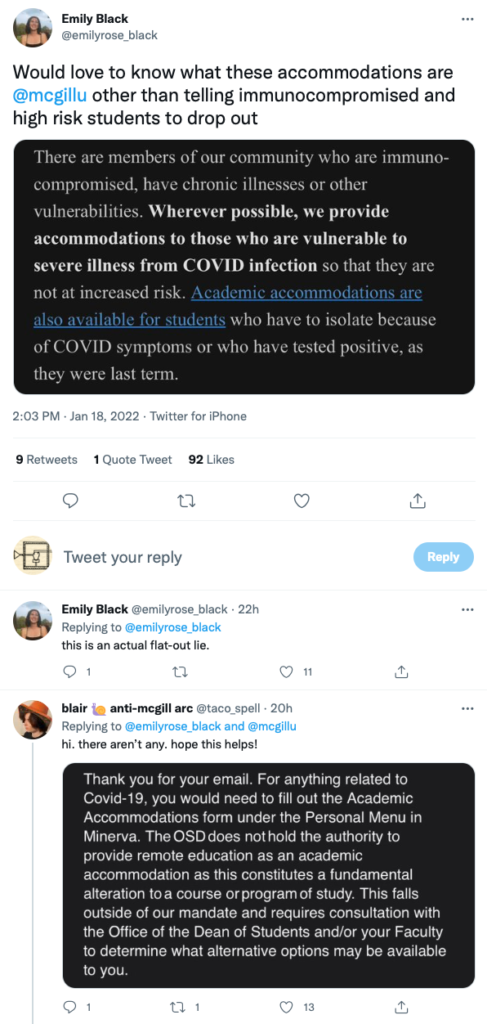

But there has been a shift since the pandemic. Now, more often, among many faculty and staff around me, protestations about busyness have taken on a tone of desperation: “help! how do I make it stop?” This is a labour-management problem. As administrations fail to replace staff and faculty, or do so with contingent or outsourced labour, more work gets dumped on everyone. It also seems admin jobs have shifted and in some cases also doubled–for instance, deans didn’t always spend so much time on fundraising. In my faculty, staff jobs have doubled and in some cases tripled in terms of responsibilities in the time I’ve been here. This has ramifications for everyone.

The solution to this problem is not complicated, but it is hard: labour organizing. Generally academic unions fight for tangible things: wages, benefits, etc. Management may concede some of these things, then create workarounds (like new job classes outside the bargaining unit). But I am curious what a quality of life academic union movement would look like.

h/t JRo

—

No, click here, not there.

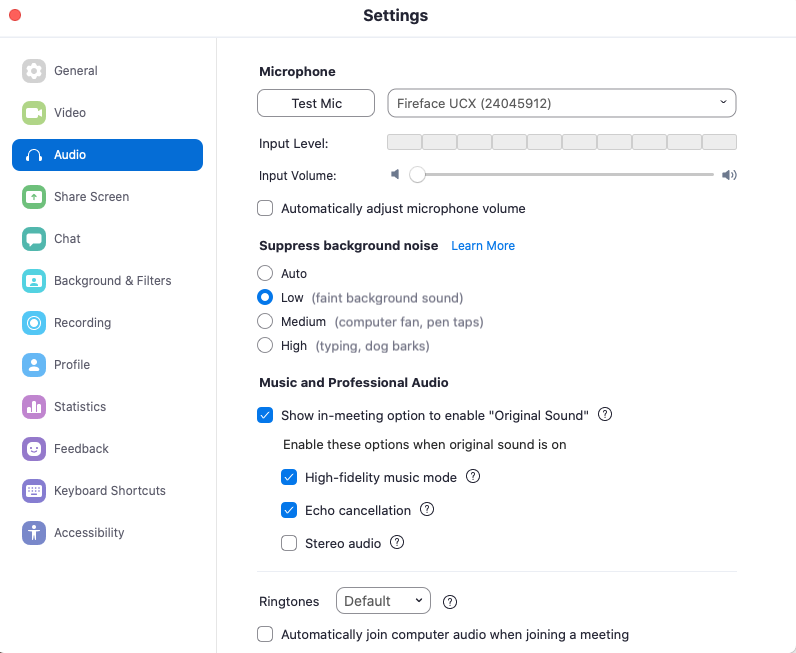

I’ve also become fascinated with the increasing reliance on software-managed work processes over the last few years. They are, quite simply, everywhere. They also add needless cognitive load and box-ticking.

In the 2010s I spent a lot of time talking with people who design software for musicians and sound artists. To the one they identified with the group they were serving, and often used their own tools. When I look at the software systems universities and grant agencies ask me to interact with, it seems they are almost never designed by — or with — the actual people who use them.

Again, I suspect this is a labour-management issue, though you’d also have to add consultancy and conglomeration to the mix. There is a tangible difference from bloatware like MS Word. It’s design actually makes no sense from the standpoint of the people who have to use it the most. (See also: Canadian Common CV.)

—

The joy of rereading old work

This week I taught Trevor Pinch and Wiebe Bijker’s “The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts” in my grad seminar. It’s interesting how things age, and what stories do and don’t get told about them. It had been a long time since I had revisited the essay. I forgot, for instance, how tentative they were about “relevant social groups” — famously sent up by Langdon Winner with his “irrelevant social groups” — and how clear they were that SCOT wasn’t just a model to stamp on everything.

Also, I could totally hear Trevor’s voice when, talking about the black boxing of scientific and technical processes, he wrote “they might as well be making meat pies.” I was supposed to be on a panel in 2004 discussing the 20th anniversary of that piece but something came up and I couldn’t go. For all the talk of FOMO, this is one of the few events I actually remember having missed.

—

Effortful Mastery

In the same seminar, we had a nice conversation about people encountering new ideas and going running for their bookshelves as a kind of defence mechanism. We’re used to being good at stuff and get impatient when we’re not.

See also: me muddling through Hard Red Spring songs on touch guitar in Tuesday’s practice. At least in Volte practice on Thursday I felt in command of the instrument and all was right in the world.

—

This comment is not promoting a product; oh shit it is

The Swedish design house Teenage Engineering, famous among musicians for a small synthesizer they make, announced a $1500(US) work table. All I can think of is the Hater’s Guide to the Williams-Sonoma Catalogue.

—

Power and Power

Last weekend we lost power for about 19 hours. On the second coldest day of the year. I did not like it. We should have crashed with friends (we had offers) or gone to a hotel. Instead we white knuckled it and slept in our clothes. Thanks to decent insulation it only got down to 13 degrees (celsius, people) but that’s pretty cold. I was very angry with the power company. I’m sure the people in Parc Ex, who were without power longer than me, had it worse. And it just shows how entitled people like me feel to infrastructure that works all the time and generally stays in the background. Everyone should have that entitlement; relatively few actually do. On the plus side, our fridge is now very clean and well-organized.

—

Not Doin McLuhan

A lot of people have a lot of feelings about the McLuhan Centre not being the McLuhan Centre anymore. Just please always remember: some of McLuhan’s most important ideas were really racist. Here’s a good thread.