Happy new year! I have boring resolutions: keep taking my cancer drugs (hardly counts–I am a compliant patient) and keep doing PT and related exercises in an effort to regain strength and endurance. (Also don’t need much motivation here.)

My 2024 in review is absurd and not worth recounting here–you can look back to older posts if you’re curious for some highs and lows. It was a year of extremes for me.

This post is mostly an update from my last post regarding strategies for living alone while chronically ill. I received some long and thoughtful messages from friends near and far, I got lot of good suggestions. Thank you friends! Every chronic illness is different so the flareups and remedies take different forms. Take what’s useful for you–that’s what I did.

Beyond monitoring and stations, here are some suggestions:

Everyone agrees with “don’t wait to take the drugs” — getting out ahead of symptoms with medications that treat them is essential and appears to be the best thing a person with any kind of flareup can do. So I will be much more aggressive with taking drugs.

On the emergency call list, people differed in terms of execution. Ellen Samuels suggested having a rotating group of people so nobody is on duty all of the time and nobody gets worn out. Sara Grimes suggested having one primary person and one backup, and giving them one another’s contact information. In the end, I am going to be optimistic and go with option 2 here. Less overhead for me. I really don’t think I’ll need the list, but better to have it.

I have already drafted an emergency document with too much information in it, and on Lisa Henderson’s suggestion, created codes for different messages so I don’t have to type anything out or try to talk. (Someone else suggested emoji). EG, 911-v is vomiting. Charming, I know. I would need to redact some things to share it publicly but if you want to see it for some reason, ping me.

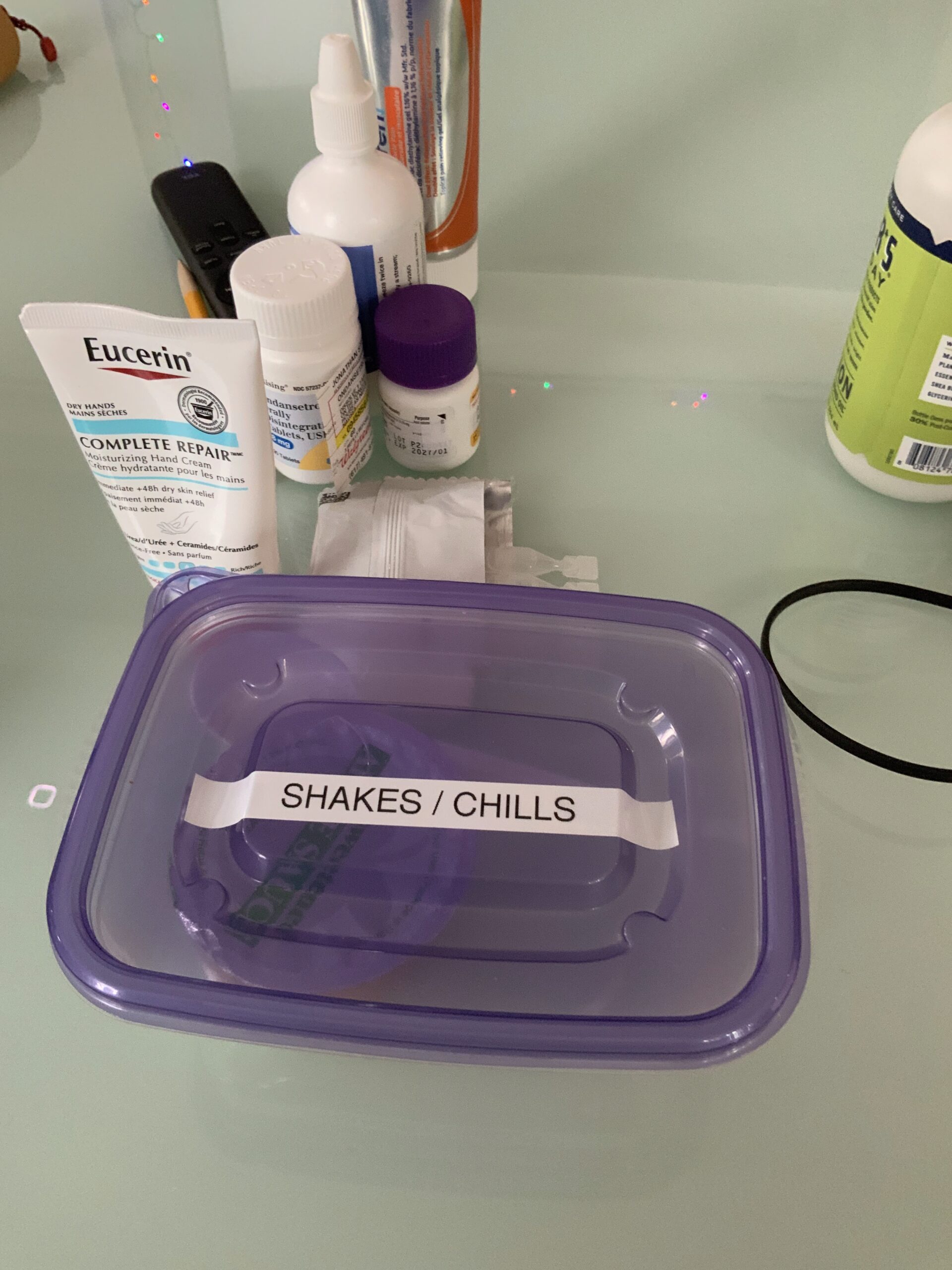

“Witchcraft list” / “Comfort Supplies”: This is the most intriguing to me, but also slightly puzzling for my situation. The witchcraft list is from Sam Thrift, who also taught me the term “migraineur,” which I love. She says she has to remember to do non-medical things to make herself feel better when having an episode. The list includes all sorts of things she can do for herself. Sara Grimes’ idea of comfort supplies is similar but objects–blankets, heating pad, etc. Ellen Samuels also suggested the heating pad for chills, and so there is now one plugged in next to the bed. She calls hers her “boyfriend.” I will need to name mine.

I am wracking my brain a bit as to what other comfort supplies/witchcraft practices would be for me, but I think self-distraction might be the way to go. Even just putting on some music. I’ve also got blankets ready to go in the living room (and extras in the bedroom).

Bringing in help: This was Sam’s suggestion. I don’t want full on home care but I do hire people to clean, change the bed, wash towels etc. And I will have friends help me carry stuff up stairs when I need that. Ellen suggested https://lotsahelpinghands.com which an interesting resource. Or a Google spreadsheet. I go this route if my needs are at all complicated. For now I’ll just text people. It seems a lot of these tools are set up for bringing people food, which I mostly don’t want or need.

(A side note: resisting offers of food is quite a job. It’s the first thing people want to do for the sick, and part of many cultural traditions. It’s the “obvious” thing to do, except in a situation like mine, it turns out.)

Old standbys: These aren’t good in acute episodes like mine, but they are good as general practices and also for episodes of depression or other “slower” kinds of flareups. Get as much sunshine as possible. Stay vigilant with meds. Practice anxiety-reducing breathing.

Techy stuff:

Alexa or other smart speaker device: Sam set this up for a relative. It allows you to operate with your voice and not have to have your phone on you to request medical support.

Extra backup phone battery in case of ER trips. Waits are long everywhere. I have one for other reasons but it’ll be useful if I needed to go.

Sara suggested a smart watch to monitor body temperature. I’m considering this one. Not sure if it’s accurate enough, and right now I’m making do with thermometers at all my stations.

—

Symptom and Side Effect Update:

It’s been a few days, so time to check in. First of all, a mental health check. As of yesterday, Carrie is in California so this whole solo thing is now happening. To say I am having a lot of mixed feelings about it would be an understatement. But it’s early days and I am figuring things out. She has sent tons of cat footage though, so that’s something. I think the issue is partly that we are on break until almost the end of the month, so it’s a lot of unstructured time and many of the other fellows are away. Whereas Carrie’s fellowship starts up again on Monday. The plan had been for me to be out there with her. But I actually do need some alone time for reflection, and I also need some time to write, so I will start leaning into that next week.

No major fevers since my last update. I do often wake up around 99.5 but I think that’s because there’s an 10-12 hour break with the Tylenol between going to bed and getting up. It goes down after I get drugs in me.

No vomiting or shakes. Yay!

This week’s mystery is extra blood in the phlegm I’m coughing up, which the nurse practitioner at the Cancer Center doesn’t seem worried about unless a lot more comes out. But my throat does feel irritated, and last night I had a long and nasty coughing fit where it felt like I couldn’t get stuff out of my throat. I have an ENT appointment later this month. I’m guessing it’s related to my irradiated pharynx, ie, cancer treatment from 15 years ago. It seems very cold things, like ice cream, can trigger it. At least I’m hoping that’s it.