You know how people sometimes post really personal stuff on social media and then say “I might delete this later?” Yeah, this is one of those posts.

The update: I am surviving ok at home. I’m in some kind of steady state where I am not in immediate danger, but I also hate this. My oxygen is still too low and I need to rest after prepping breakfast or cleaning up thereafter. The coughing fits also just kill me. I am still having trouble swallowing and have to eat and drink very slowly and intentionally or my throat goes into spasm and I gak (<–my technical term). Relearning how to eat is hard! But I think my throat is healing some as there is now almost no blood in my phleghm. I am still in that phase of figuring out what med to take when. Yesterday my heart rate was all up and down in a most unpleasant fashion. Today it’s more steady because–I think?–I timed my new asthma drugs differently.

I am being well looked after by friends. I can socialize for a few hours as long as I am just sitting, and the people around me don’t mind an absolutely horrific coughing fit from time to time. I was ferried to a friend’s house last night for the US VP debate, which was predictably awful, but I had a wonderful time with the company. I am determined to go for a short walk today, with my cane, at whatever speed is slow enough, just to get some fresh air. Radcliffe has been great so I can at least remotely tune in to other fellows’ talks.

Doctoring: tomorrow I see the pulmonologist, Friday morning, I establish primary care, and the following Friday, I meet a local oncologist who is a world expert in my condition.

Carrie arrives late Friday afternoon, which will be fucking great.

—

A Detour Through Existentialism to Explain My Attitude:

In response to reading my writing about illness, some people ask me about the style with which I write. Some call it “optimistic” or “upbeat” or “inspiring” (<–I know this is a banned word in disability land but let’s give people some grace). How, they ask, do I maintain such a positive attitude?

Here’s your answer: existentialism. My suffering is utterly, inherently, fundamentally, meaningless. It is not a cosmic punishment for anything. It is also not a challenge thrown before me to improve my character. It offers me no moral authority, and it does not morally degrade me in any way. It just is. I have no motivation to lean into it or to continue to suffer.

Writing about my own illness, even making fun of it, is a way of giving it shape and form. Intellectualizing it–to a degree–helps me feel some distance, and offers me whatever perspective I need. Of course I have to be able to do that. The first couple days of hospitalization last week made that impossible. Now I have time to reflect, so I narrate.

As you may know, existentialism is a baggy collection of philosophies (and philosophers) who argued that for people, the primary challenge of existence is coming to terms with its givenness and with their own mortality. It is a rejection of the metaphysical meanings imposed by organized religion, as well as the social meanings often imposed by institutions <–This is a gross oversimplification but this blog is not where I am going to parse Jaspers, Buber, Heidegger, Sartre and de Beauvoir. Nobody wants that.

I think my conversion moment happened 12th grade in Mr. Mossberg’s humanities course. I was raised Jewish and to be Very Jewish. Because it was determined that I was good at book learning, I was supposed to pious, and was subjected to years of Hebrew school after school and on weekends. To me, so much of the religion I was being taught seemed hollow, authoritarian, and without any real meaning or joy (my views on religion have evolved but this is what I felt at the time). I did, however, get my love of close reading and footnotes from Mr. Blackman, who specialized in Qabbalic readings of scripture, so big thanks to him for that. Anyway, the Jewish education didn’t take, and neither did the Zionist education — but that’s a story for another time.

I was a person without religion, despite having been given a whole lot of it up to about age 14, when I finally convinced my parents to let me stop going to Hebrew school. This is where Mr Mossberg’s class came in. It was greatest hits of Western philosophy. We read a little Camus — I think — and then watched a filmstrip in class. In my mind, the filmstrip is the conversion moment. It was all in blue and brown hues. The illustrations were all that sort of empty post-war European modernist vibe tinged with the lonely overtones of American painting and social theory, and the music might as well have been Schoenberg. Knowing what I know about film and TV history, let’s say this filmstrip was made in the 1960s, and being shown in 1988 0r early 1989. It went something like this.

[Opening slide, including portentious title about existentialism, and some kind of overture.]

DING

[Man walking alone in the rain, in the city. Definitely wearing a hat and an overcoat.]

“Man must reckon with a simple fact. One day he will die.”

DING

[Another image of “mass man” walking in a crowded city, but utterly alone.]

DING

“Life has no meaning that is given to us. It is up to us to determine its meaning.”

DING

..and so on.

My 18 year old mind basically exploded. Here was a worldview that implied both freedom and absolute finitude, and that made clear both conditions imposed demands on the subject. I don’t claim that I fully understood all that either then or now. But this basic perspective has shaped my towards my own illness, my relationships to others, my relationship to others’ beliefs that are not my own (I consider myself the world’s least militant agnostic), to the various emotional and psychological struggles I’ve had in adulthood, to my sense of justice and fairness.

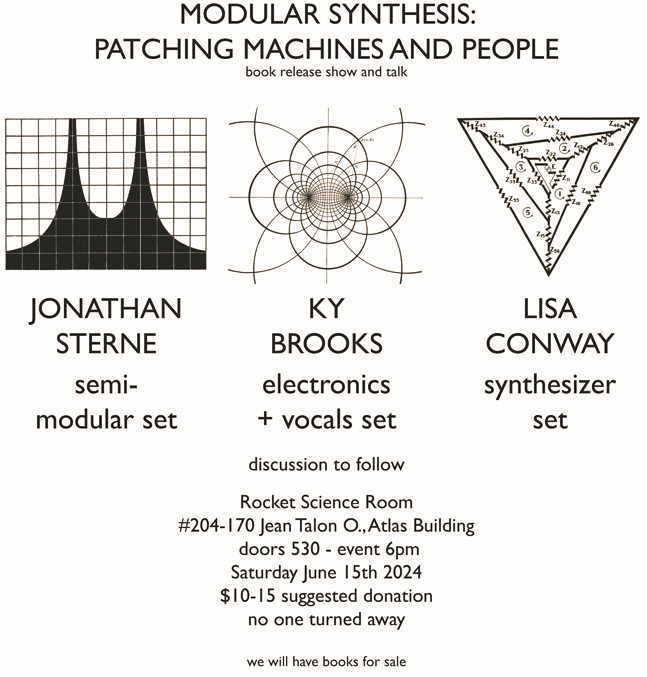

As narrated in that filmstrip, and in some of the more macho writings in the tradition, I think existentialism gives the subject too much credit and too much power. And its universalism is probably indefensible from any modern theoretical position. With cancer, anyway, apart from being a compliant patient, I’ve really ceded control to my doctors and those around me, and to the illness itself. Maybe my interest in modular synthesis lines up with that–an endless exploration of the possibilities of control in another space in my life as a sort of compensation, I don’t know.

Intellectually, I don’t do much with this strain of thought in my scholarship, apart from some edges of the phenomenology in Diminished Faculties. I’m too uncomfortable with the tradition’s universalism and I haven’t found existentialist writers with whom I connect politically. I prefer more radical and collectivist traditions.But I think that filmstrip somehow does a good job of explaining why I react to my illness the way I do. I can savour the moments of happiness and connection in my life even as I am suffering because I see those two things as morally unrelated. They can simply coexist.

There is also a disability studies critique in here. Western medicine, and its reflection in popular culture, is incredibly moralistic. It implies people have much more control over their health than they do. It implies that the sick, the dying, the injured, are a burden on the healthy, rather than a turn that we all take if we live long enough. This also means I have become shameless about asking for help when I want and need it, with the caveat that the help I want isn’t always the “standard” help that people expect to want.

So in asserting that there is no given meaning to my illness, I am emphatically rejecting the moralistic worldview of illness and debility and everything that goes with it. At the same time, I have had people say they felt bad about feeling bad about going through whatever they were going through while I was dealing with my mess “so well.” I’m sad to hear that. Misery has no means test. It’s normal and fine to be unhappy when you feel like shit. I spend a good chunk of my day annoyed at my limitations right now and feeling like I’m missing out on the joys of sabbatical. What I wouldn’t give to be able to go into the office every day right now! But that’s not the only thing I feel, and so I just try to go out there and confront the whole catastrophe.

All I can say is that it works for me, for now. If I’m true to that existentialist kernel, then that also implies how I think about it for others. This might not work for anyone else. It’s up to you to figure out what works for you.